Remember the difference between weather and climate? We know what happens when the weather changes—it’s obvious. Climate is another story. Read on.

When it rains, you put on a raincoat or take your umbrella when you go out. It snows: time for high boots, a heavier coat, scarf, and warm gloves. And sunny days, well, they’re the best for being outdoors, unless it’s noon in the tropics. What’s more difficult for us to perceive, from the relatively short perspective of one human lifetime, is that like weather, climate changes too.

What is climate change? On historic maps, we see climate change in the advance and retreat of glaciers, the transitory nature of coastlines, and the periodic appearance and drowning of islands. Species change in response to it. Scientists have learned to measure these climate fluctuations using treetrunk rings, snow lines, fossil records, and cores of ancient ice or seabed. In the past 50 years, we have even devised sophisticated satellite instruments to reveal changes in earth’s land, air, water, and ice, or in the sun and the energy it puts out.

All these measurements have taught us that Earth’s climate changes naturally. Over the past million years there have been a number of cold stages, or “ice ages”— cooler times when much of earth’s water has frozen into ice caps covering the poles and glaciers extending from them toward the tropics. (Inset: The Weichsel: our previous ice age, from math.ucr.edu)

During the interglacial periods, which are shorter than the icy ones, earth’s temperature rises and the snow and ice melt, increasing sea levels.

Around the end of the last ice age (the Weichsel, above), the earth transitioned into the benign interglacial climate of the Holocene epoch. At this time, a land bridge called Beringia existed between Siberia and Alaska. It enabled east Asian migrants to become “native Americans.” Through Dutch fishing boats and recent North Sea oil drilling, we have discovered that around the same time, humans could walk from the current nation of Holland all the way to the Irish Sea. Before the English Channel formed, Great Britain was a peninsula linked to the rest of Europe by a low, ecologically rich plain called Doggerland. Over only ten thousand years or so, a temperature rise of 4 degrees C. and accompanying sea level rise of only a few hundred feet eliminated both of these bridges between continents.

Scientists have various theories about what makes climate so fickle over the long run. They’ve found any or all of these factors important to some degree to the question of what is climate change.

- Variations in the sun’s energy output, measured as changes in the amount of radiation it emits.

- Small changes in earth’s orbit (Milankovitch cycles) caused by the variable tilt of the planet, its slightly eccentric orbit, and its axial (gyroscopic) precession.

- Orbital dynamics of earth and moon.

- Motion of earth’s tectonic plates with seismic activity (drifting continents), which changes the relative locations of landforms and affects wind and ocean currents.

- Impact of meteorites—not small phenomena like the recent ones in Russian, but relatively huge masses like the six-mile (10-km) Chicxulub asteroid that smacked into Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula 66 million years ago. Its impact sent millions of tons of material high into the atmosphere, blacking out the sun for months. It caused the earth’s last great extinction, abruptly and forcefully wiping out all dinosaurs without wings, ending the Cretaceous period of life on the planet, and paving the way for the Cenozoic and the emergence of mammals.

- Volcanic mega-eruptions, especially from the prehistoric caldera-forming colossi in the American West near Yellowstone, the North Island of New Zealand, subtropical and temperate South America, and potentially from the massive igneous province forming in Iceland. Supervolcanoes like these help determine what is climate change. They send huge amounts of ejecta (ash, gas, and aerosol droplets) into earth’s stratosphere. (Even historic, relatively small eruptions at places like Mauna Loa in Hawaii [33 eruptions in the past 170 years], Indonesia’s Krakatoa [1883], Mount St. Helens, Washington [1980], Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines [1991], and Iceland’s Eyjafjallajoekull [March 2010] figure into what is climate change because they have disturbed the atmosphere and temporarily cooled the earth.)

- With meteorites and volcanoes, we can watch earth’s atmosphere in flux, as visible particles crowd the skies. But along with them comes an invisible, and possibly invincible, alteration in the atmosphere—in the gases that comprise it, including its concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane. We can see these influences in the deep Vostok ice core samples from Antarctica that record atmospheric composition over the past 800,000 years.

On this final accompaniment of climate change—atmospheric variation—today’s research is nearly unanimous (97%). What is climate change? A lot of the phenomenon has to do with the effects of increasing certain atmospheric gases. The temperatures on earth’s surface (land and oceans) are directly related to the chemical composition of our planet’s thin atmospheric shell.

Climate shapes and alters natural ecosystems. By doing so, it affects the rise and fall of human civilizations. It governs where and how people, plants, and animals live. It juggles the water, food, and health of its inhabitants. Within the brief time of recorded history (last green bar above), our climate has been relatively stable. It has been generous to human life, allowing exploration, trade, development, labor-saving invention, and even space flight and greater awareness of our universe.

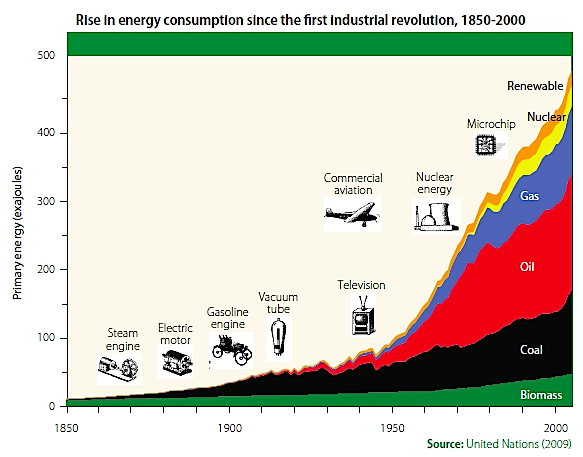

But over the past 200 years, as humans industrialized and populations grew rapidly, the formerly placid natural phenomenon of climate change has been occurring at a much faster rate. We know from meteorological records kept since 1880 that the planet’s temperature has risen about one degree Fahrenheit in the last century. The results of this apparently small change have been impressive. We’ve seen more snow and ice melt, a rise in ocean levels, intensifying storms, and changes in crop seasons and animal reproductive and migration schedules.

In fact, over the past couple of decades, scientists have started saying we have switched over from the Holocene to the Anthropocene (human-centered) epoch, and the polar bear on a shrinking ice floe has become a visual cliche. None of the natural causes discussed earlier can fully explain the climate changes we are seeing today. The accelerating temperature results from a massive new influence shaping world climate—the human factor.  Our expanding quest for and use of energy has given people the ability to alter the climate. Our own Promethean activities now alter the balance of gases that trap the sun’s heat within the atmosphere, which until now has been earth’s protective greenhouse. Amounts of carbon dioxide, the most common greenhouse gas, are rising sharply to a level unmatched in the past 650,000 years, and other potentially harmful gases like methane are increasing, too. What we commonly call “nature” still makes up much of the force behind climate, but almost all the world’s scientists now say that humans can change climate also. Expanding populations produce and cook food. We drive cars. We heat and cool our houses mechanically. We construct and use factories. All our activities consume energy.

Our expanding quest for and use of energy has given people the ability to alter the climate. Our own Promethean activities now alter the balance of gases that trap the sun’s heat within the atmosphere, which until now has been earth’s protective greenhouse. Amounts of carbon dioxide, the most common greenhouse gas, are rising sharply to a level unmatched in the past 650,000 years, and other potentially harmful gases like methane are increasing, too. What we commonly call “nature” still makes up much of the force behind climate, but almost all the world’s scientists now say that humans can change climate also. Expanding populations produce and cook food. We drive cars. We heat and cool our houses mechanically. We construct and use factories. All our activities consume energy.

Since the Industrial Revolution, we have obtained energy through the quick fix of mining and burning our limited reserves of coal, oil, and gas. It’s a bit like raiding the kitchen in the middle of the night. Where there’s fire, there’s smoke, though. Look at the “hockey stick” plot of global temperature (right). It shows that instead of continuing the downward trend toward another ice age—which the historical record indicates we should expect—temperatures are rising, and rising very fast.

Burning for energy changes the atmosphere by raising levels of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases. And changing the atmosphere changes everything.

The bottom line is that we no longer know what to expect from our climate. Extinction of many species (including our own) is a possibility. We cannot calculate the amounts of greenhouse gases that will enter the atmosphere, how much and how quickly warmer temperatures will lead to other changes, or even what will be going on in our own backyards by 2050.

It’s not just nature that’s running the show any more. The rules have changed. The compositions of our air, land, and seas are in metamorphosis. We find ourselves conducting an unplanned and potentially vast experiment as we segue from the Holocene into the Anthropocene. We can no longer use our wisdom from earth’s past to discern what the future will bring.

This is the first time humans have been capable of causing major climate change on our planet. However: this is also the first time we have had the opportunity to alter its course.