Scientists have detected a new type of El Niño that is forming in the warmer waters of the central-equatorial Pacific Ocean, causing the El Niños to become more common and stronger. Researchers found that the intensity of El Niños has nearly doubled in the central Pacific.

The research, conducted by Tong Lee of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., and Michael McPhaden of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, Seattle, will hopefully improve our understanding of the relationship El Niños play on our environment, specifically on climate change, and increase our ability for long-term weather forecasting.

“Our study concludes the long-term warming trend seen in the central Pacific is primarily due to more intense El Niños, rather than a general rise of background temperatures,” said Lee.

“These results suggest climate change may already be affecting El Niño by shifting the center of action from the eastern to the central Pacific,” said McPhaden. “El Niño’s impact on global weather patterns is different if ocean warming occurs primarily in the central Pacific, instead of the eastern Pacific.

“If the trend we observe continues,” McPhaden added, “it could throw a monkey wrench into long-range weather forecasting, which is largely based on our understanding of El Niños from the latter half of the 20th century.”

El Niño is Spanish for “the little boy,” and is part of the El Niño/La Niña-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, a “quasi-periodic” climate pattern that takes place across the Pacific Ocean every five years, on average, but which can vary from three to seven years. El Niño is Earth’s most dominant year-to-year fluctuating climate pattern, and can impact everything from global weather patterns, the frequency of hurricanes, droughts and floods, and even as important socioeconomic consequences.

From the JPL announcement of their research;

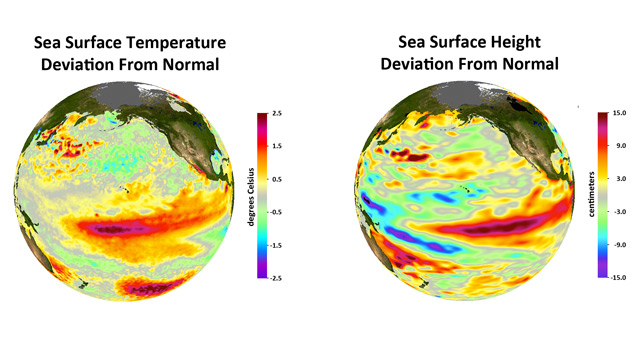

During a “classic” El Niño episode, the normally strong easterly trade winds in the tropical eastern Pacific weaken. That weakening suppresses the normal upward movement of cold subsurface waters and allows warm surface water from the central Pacific to shift toward the Americas. In these situations, unusually warm surface water occupies much of the tropical Pacific, with the maximum ocean warming remaining in the eastern-equatorial Pacific.

Tong Lee and Michael McPhaden have measured changes in El Niño intensity since 1982 using NOAA satellite observations of sea surface temperature and checking them against and blended with directly-measured ocean temperature data. The strength of an El Niño was determined by how much its sea surface temperature deviated from the average.

Scientists the world over have been identifying a stronger central-pacific El Nino, known variously as “warm-pool El Niño,” “dateline El Niño” or “El Niño Modoki” (Japanese for “similar but different”), where the maximum ocean warming is found in the central-equatorial region rather than the eastern. Such central Pacific El Niño events were observed in 1991-92, 1994-95, 2002-03, 2004-05 and 2009-10.

Lee said further research is needed to evaluate the impacts of these increasingly intense El Niños and determine why these changes are occurring. “It is important to know if the increasing intensity and frequency of these central Pacific El Niños are due to natural variations in climate or to climate change caused by human-produced greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.

Source: JPL