For anyone still confused about this, here’s a great post by Joe Romm of Climate Progress reposted in full below. The post, based on a new study, also tackles other common myths the global-warming-denial contrarians love to spread and many greens will even parrot.

Other big points are that Obama’s silence on global warming is a big failure, and that media coverage of climate change is very closely linked to public concern about climate change. Also, major reports (e.g. by the IPCC) and scientific magazines have a statistically significant effect on public concern.

Anyway, here’s the full piece, titled “Exclusive: “Exciting” Public Opinion Study Debunks Claim Al Gore Polarized the Climate Debate and Many Other Myths“:

by Joe Romm

Public Opinion Driven Largely by Media Coverage and Cues from Politicians and Other Authorities. Obama’s Silence Matters “Very Much.”

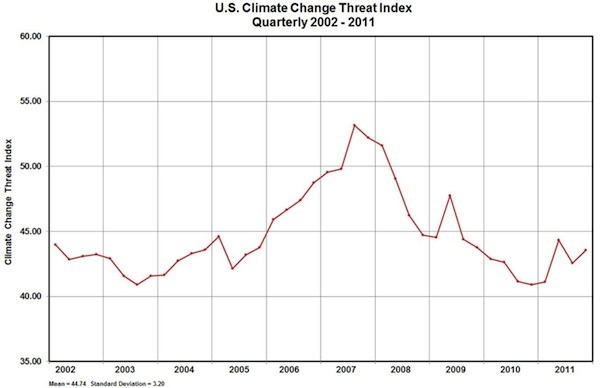

The Climate Change Threat Index (CCTI) aggregates data from 6 different polling organizations gauging how much people worry about global warming

A must-read study published Monday in the journal Climatic Change debunks some pervasive myths about public opinion and climate change. The lead author, Dr. Robert J. Brulle of Drexel University, gave me an exclusive interview.

Stanford’s Jon Krosnick told me this paper was an “exciting contribution to the growing literature in this area.” He said, “the results he produced line up very closely with the results of our surveys and with my thinking on the issue, with a couple of caveats,” which I discuss below. He believes, “this paper represents a terrific amount of excellent work and is a great contribution to the literature using a well-established method.”

Here are some of the key findings from “Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010″:

- “… media coverage of climate change and elite cues from politicians and advocacy groups are among the most prominent drivers of the public perception of the threat associated with climate change”

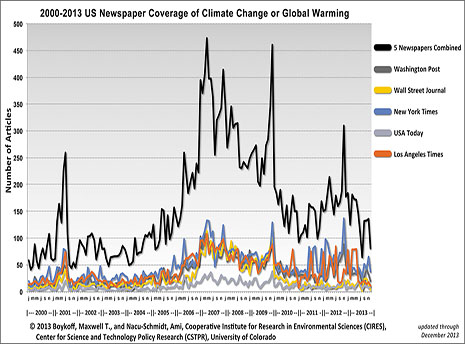

- “The greater the quantity of media coverage of climate change, the greater the level of public concern.”

- “New York Times mentions of An Inconvenient Truth significantly boosted the public’s perception of the urgency of climate change (P≤.001). The number of mentions in the New York Times is a proxy for the extent of overall media attention to this film.”

- “Articles in popular scientific magazines do reach significance” in terms of influencing public concern, but it is a modest effect

Media coverage of climate change accounts for almost half of the variance in the CCTI, which isn’t terribly surprising when you compare the top chart with a graph of media coverage:

This finding shouldn’t surprise anyone. I just started reading the best-seller Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist who won the Nobel prize in economics. He explains:

People tend to assess the relative importance of issues by the ease with which they are retrieved from memory– and that is largely determined by the extent of coverage in the media. Frequently mentioned topics populate the mind even as others slip away from awareness.

Brulle’s study also finds that the public’s relative concern about global warming is affected by “structural economic and political factors play a major role”:

An increase in the unemployment rate significantly decreases the CCTI, and conversely, an increase in GDP significantly increases the CCTI. The number of U.S. war deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan significantly decreases public concern about climate change (P≤.05). These findings suggest that when there is a shock to the economy or intensification in the wars, the general public may reduce their level of concern about climate change.

I interviewed Brulle, whom the NY Times has called “an expert on environmental communications,” about his paper. Here are some of his comments:

- “I think this should close down forever the idea that Al Gore caused the partisan polarization over climate change.”

- “The fact that Obama isn’t talking about the issue or even using the word matters very much.”

- “Popular scientific magazines and the release of major reports (NRC and IPCC) do have a statistically significant effect.”

- “The only messaging campaign that works is one that is consistent. It has to be, especially since it is facing an opposing campaign that is much better funded.“

I have previously pointed out that extensive polling data simply doesn’t support the widely-held myth that Gore polarized the debate (see “Polarization on Climate Jumped in 2009 — Long After Gore’s 2006 Movie“). I’ve asked many leading experts on social science and public opinion — including McCright and Dunlap, authors of “The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010″ — and they all agree the data don’t support this myth. I just asked Krosnick the same question, and he also agrees there is no data to support it.

Indeed, the data actually suggest the reverse, that, if anything, Gore’s movie and his “We Campaign” to bring together well-known figures on both sides of the partisan divide, actually decreased polarization temporarily:

Percent of Americans Who Believe the Effects of Global Warming Have Already Begun to Happen, by Political Ideology, from McCright and Dunlap

This new study confirms that view — that Gore’s movie and his efforts helped drive up public awareness and concern about this issue across the ideological spectrum.

Because this study should inform climate communications efforts going forward, let me review the key findings:

Media coverage is crucial:

First, media coverage of climate change directly affects the level of public concern. The greater the quantity of media coverage of climate change, the greater the level of public concern. This is in line with the Quantity of Coverage theory of media effects, and existing individual level research on the impact of television coverage on climate-change concern. The importance the media assigns to coverage of climate change translates into the importance the public attaches to this issue. Second, in a society with a limited amount of “issue space,” unemployment, economic prosperity, and involvement in wars all compete with climate change for public concern.

So are “elite cues”:

The most important factor in influencing public opinion on climate change, however, is the elite partisan battle over the issue. The two strongest effects on public concern are Democratic Congressional action statements and Republican roll-call votes, which increase and diminish public concern, respectively. This finding points to the effect of polarized political elite that is emitting contrary cues, with resulting (seemingly) contrary levels of public concern. As noted by McDonald (2009: 52) “When elites have consensus, the public follows suit and the issue becomes mainstreamed. When elites disagree, polarization occurs, and citizens rely on other indicators, such as political party or source credibility, to make up their minds.” This appears to be the case with climate change.

The study has other interesting findings. First, extreme weather — or at least the metrics the study used to stand in for extreme weather — did not have a statistically significant impact on public opinion:

Model 1a tests the influence of high temperature, precipitation and drought. Model 1b uses the Climatic Extremes Index developed by NOAA, which includes six indicators of weather extremes. Two separate models were run because the Climate Extreme Index is a composite index that includes the three variables in model 1a. Neither specification was statistically significant, suggesting that weather events, in themselves, do not influence the overall level of public concern regarding climate change. That is not to say that individuals who experience disruptive weather events do not change their opinions regarding the threat posed by climate change. However, the extent of these changes has not reached a level where these shifts can be measured in nationwide polls at the aggregate level. This result may change over time if weather disruptions attributable to climate change increase.

I think these results make sense, but I’m not sure those are the best metrics. Also, the study unfortunately ends in 2010, and both 2010 and 2011 were years of record-smashing extreme weather, particularly for this country. I tend to think it is the uber-extreme events that are most likely to influence public opinion — the monster events that scientists projected would become more frequent and extreme — super heat waves, droughts, wildfires, superstorms and floods.

But of course the media would need to explain to the public the connection between the extreme events and global warming, which they aren’t doing a good job of. Indeed, one key point of the study is that the media mediates a lot of the public’s exposure to and understanding of the climate issue. Were the media to cover the link more, it might well move the needle.

Model 2 tests the hypothesis that the availability of scientific information will lead to an increase in public concern. The model controls for the number of climate change articles in Science, popular scientific magazines, and the release of major climate change scientific assessment reports. We found that the number of articles in the journal Science does not have a significant direct effect on public concern. Because Science articles are generally not read by the general public, it is not surprising that they have no discernible direct effect.The release of major scientific assessment reports is marginally statistically significant (P≤.1). The release of these reports produces an increase in the CCTI of 2.5 points. Articles in popular scientific magazines do reach significance (P≤.01). The publication of an individual magazine article in this forum increases the CCTI by .2 points.

I have two issues here. First, I’d like to have seen a metric of mainstream media coverage of science, rather than just science magazines.

Second, relatedly, I’d argue that An Inconvenient Truth is mostly a science documentary, since the movie itself has virtually no politics or policy recommendations in it. Thus I suspect mentions of the movie in the NYT correlate with science communications with the public. One would have to go back and check that the NYT (and other MSM) articles on the movie focused on the science. Also the IPCC Fourth Assessment happened to be released in 4 parts in the year following the movie and 2007 was the peak year for public concern. It was probably the peak year for coverage of climate science.

I put this question to Krosnick and he wrote:

You are putting your finger on an important issue in this sort of study – there are always judgment calls to be made, and you’re right that the Gore movie needs to be categorized somehow. I guess the operative question is whether what matters is the substance of what was said (results of scientific studies) or who said it (a politician, not a scientist). That’s testable empirically, of course.

Here are more of Krosnick’s comments:

Robert’s paper is an exciting contribution to the growing literature in this area.

He used a well-established method for conglomerating the results of different surveys.

And the results he produced line up very closely with the results of our surveys and with my thinking on the issue, with a couple of caveats.

First, his pattern of increase and decrease in public thinking (I’m going to use the ambiguous word “thinking” for the moment) with a peak in 2007 matches our data:

National survey of American public opinion on global warming via Jon Krosnick, Stanford University

We see a decline from 84% in 2007 to 75% in 2009, 9 percentage points.

He sees a decline from about 52 or so in 2007 to maybe about 46 in 2009 (averaging his numbers across each year), a 6 percentage point drop.

And he finds the same stability from 2009 to 2010 that we see in our data.

Yes, his text takes Figure 1 quite literally and talks about a larger drop. But the little ups and downs in the curve are not statistically significant, so I would be cautious about interpreting them.

Second, his conclusions that media coverage and elite cues match well with what we’ve seen in our own research. In fact, if the agenda-setting hypothesis hadn’t been supported here, it would have been a big surprise, in light of so much evidence published to support it regarding other issues.

His conclusions that other factors, such as extreme weather events, are not influential, comports well with my thinking on the issue, though I have no direct evidence to support that intuition.

My only hesitation about the paper is one that I’m sure Robert shares as well – using the Stimson method leads to the construction of what Robert and colleagues call their “”threat index”. The paper does not report the exact wordings of the questions that compose the index, and it won’t surprise you to know that the wordings would matter to me. The wordings are in the supplementary materials. They ask:

- How much the respondent worried about GW

- How likely the R is to be personally affected by GW

- Whether GW is having a serious impact now

- Importance of GW to the respondent personally

- Seriousness of GW as a problem for the US

- Seriousness of GW as a problem (not specifying for whom)

- Whether a 5 degree temperature rise in 75 years would be bad

- Whether news coverage exaggerates the seriousness of GW

- How soon the effects of GW will appear

- How threatening GW is to the vital interests of the US

As you can see, this index mixes lots of different types of questions together. Other questions that could have been included (e.g., seriousness of GW as a problem for the world) are omitted, and one could make arguments about whether some of these questions belong in an index with the others (e.g., given a great deal of work suggesting that people think differently about their own personal risks than they think about national or global risks, does it make sense to blend questions about personal impact with questions about national impact into an index?).

When different questions get mixed into an index like this, I’m not sure (1) what the index is really measuring, and (2) how robust the results would be to changes in which question are used.

Regardless, this paper represents a terrific amount of excellent work and is a great contribution to the literature using a well-established method.

Kudos to Brulle and his coauthors for this important paper.

UPDATE: Brulle responds to Krosnick:

I do agree with Krosnick that the aggregation of questions needs work. This is just the first time out using Stimson’s method to aggregate concern about climate change from a number of polls, and so we need to do further work on that area. However, the questions in the index do load very well, and the index accounts for about 80% of the variance in the responses to the questions.

Firstly, politicians ALWAYS deny the existence of ANY problem…

Secondly, mankind is stuck in its comfort zone…

Everything is just too easy – so why bother to change it? It’s just like people who smoke – the results are not visible yet, so why worry?

It’s scary to think how little sense of responsibility we actually have…

just my 0.02c

peter

true

true

and yes, it is, isn’t it.

i have never seen statistics on the amount of pollution created before we even pump a gallon of gas into our car.

if we compared the actual amount of pollution created by a gallon of gas compared to electric vehicles it would have a greater impact.